Tech Post: Dark Matter

A hot take from an amateur cosmologist

I started this week thinking I’d write a tech post about delta-v and the various things that impact it, but it turns out that topic is delightfully complicated, and my thoughts need to percolate for a while for me to get the discussion right. So, instead, this week’s tech post will be a speculative hot take on the nature of dark matter.

As an intro, dark matter is a cosmological placeholder, which means that we don’t actually know what it is. What we actually know is that galaxies look like they have more gravity than they should, particularly in their outskirts.

Here’s the theory: When a small mass orbits another much bigger mass, you can measure the orbital velocity and the orbital radius, and it tells you the mass of the bigger object. At any given radius, the gravity of the center mass exerts a specific amount of gravitational force, there is a specific orbital velocity that is necessary to achieve a stable orbit. The further the small object is from the big object, the slower that velocity gets (because the orbital circumference grows linearly, but the force of gravity drops off exponentially). So, if you can find a small object in a stable orbit around a big object, you can figure out the big object’s mass.

Galaxies are big objects. The stars in them are much smaller, are rotating around the galactic center, and are quite bright which makes them easy to see and their orbits easy to measure. Perfect tools to estimate the total mass of the galaxy.

[Pictured: A galaxy. Not Pictured: Dark matter. It’s invisible, you see.]

We also have other ways of estimating the mass of galaxies, such as by using them as gravitational lenses to bend the light from other galaxies further away. We can look at how much the light beams get bent as they pass through the gravitational field of the galaxy, and calculate how much mass would be needed to bend the light that much, and thus approximate the total mass of the galaxy.

Thirdly, we can just look at the stars. Stars shine because of the nuclear fusion reactions happening in their cores, heating them up. The heavier the star, the more dense the core, which causes both faster fusion reactions and reactions involving a wider variety of elements. More fusion, hotter star. Hotter star, bluer emitted light spectrum. The light spectrum also tells us a lot of information about the star’s composition, so we also generally know what fuel the star is burning, and because we have a decent understanding of nuclear physics as a civilization, we know how much energy is produced by burning that fuel, and how much and how fast it would need to burn to get as hot as the light the star is putting out. Thus, just by measuring the light output of a star, we can estimate its mass. Add it up across a galaxy, and you get a rough estimate of the mass of the galaxy.

The trouble is, with all these methods, we get crazy answers. Just adding up the mass of the stars gives us an estimate that is about 5x lower than if you use gravitational lensing or rotational velocity methods. Gravitational lensing roughly agrees with the rotational velocity method, but the specific results within any given galaxy are really weird - instead of the outermost stars orbiting the center more slowly than inner stars, they usually orbit at the same or higher velocity.

[Left: What we observe happening, with nearby galaxies. Right: What our understanding of physics says should be happening, and also what we observe in very distant galaxies from 10 billion years ago.]

To sum up the problem, galaxies are acting like they are about 5x heavier than they should be based on the stars and other material (gas, dust, etc.) we can see in them. The simplest explanation is that there is a bunch of heavy matter that we can’t see because it doesn’t absorb or emit any light…. i.e. “dark matter”.

Dark matter cosmologists have been looking at the various data, and have some theories:

WIMPs.

[Image not found, largely because WIMPs have not been found either.]

WIMPs are Weakly Interacting Massive Particles, which are theoretical particles that only interact by gravity and forces at least as weak as the weak nuclear force, have mass, and don’t absorb or emit light, so we can’t see them. However, if they exist, their should be matter WIMPs and antimatter WIMPs, which should be able to annihilate each other and release specific types of gamma rays. We’ve been looking for those gamma rays for a couple decades now, long enough that if WIMPs are as common as they would need to be if they are what dark matter is made of we should have seen them by now. We haven’t seen them.

Neutrinos.

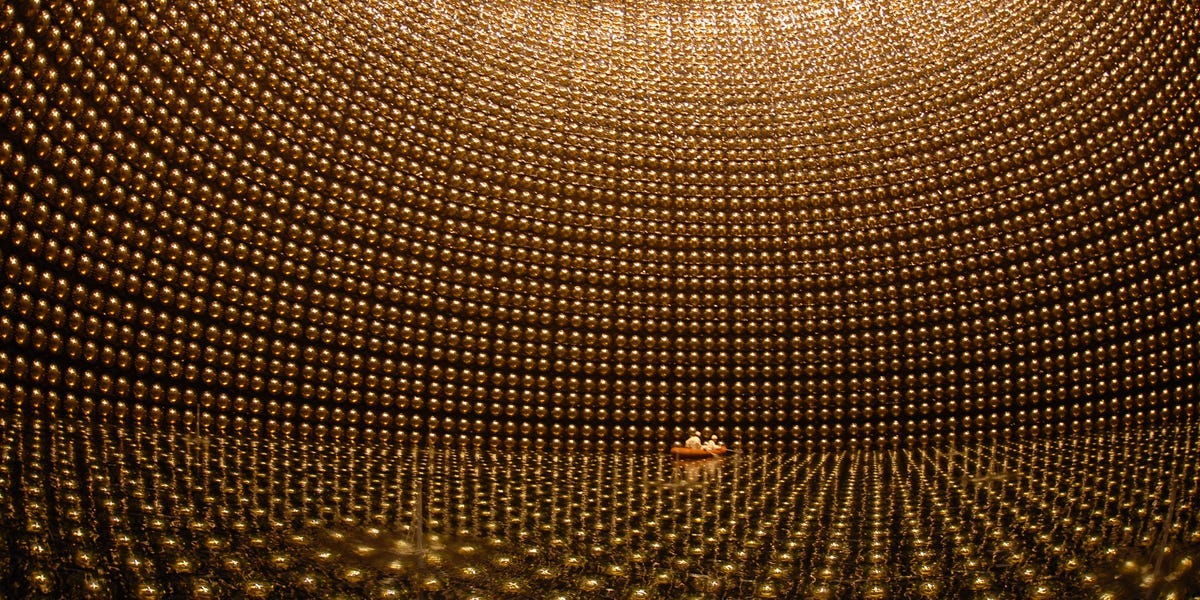

[This is the Super Kamiokande neutrino detector buried a kilometer down under a mountain in Japan, which is quite possibly the coolest looking scientific facility on Earth. Neutrinos will very, very occasionally hit water molecules (hence the pool), and emit light (hence all the photomultiplier detectors on the walls).]

Neutrinos are similar to WIMPs, except with less mass. They interact mainly via the weak force, and they similarly do not absorb or emit light except when they annihilate in matter-antimatter reactions. We know there are a lot of neutrinos out there, and we also know that they do have some amount of mass, but it is much, much less than is proposed for WIMPs. As a result of their incredibly tiny mass, neutrinos move fast, like, pretty close to light speed. The result is that they are considered a poor candidate for dark matter; they almost always have escape velocity from whatever body emits them, which means their mass distribution in space is predicted to be all spread out. That’s a lot different from what the galaxy orbital motion data implies as the distribution of dark matter, which seems to be all lumped together, mostly in the outer reaches of galaxies.

Black holes.

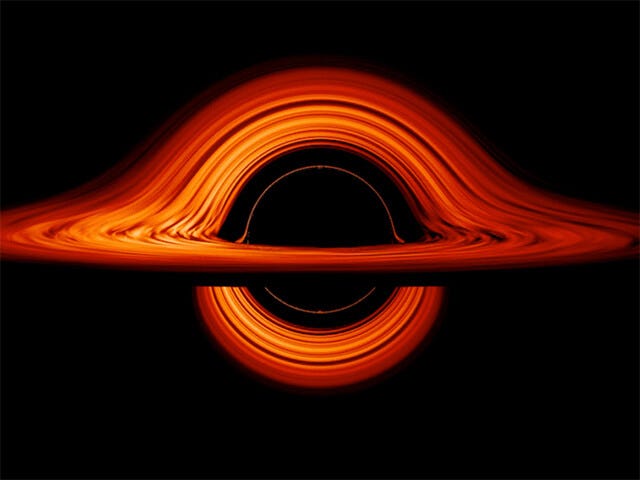

[Black holes actually look like this. The debris disk orbits fast and hot, emitting light. Because the black hole warps spacetime, the light from the part of the debris disk behind the black hole is bent around it, visible to us as a bright halo both on top and on bottom of the dark center.]

Black holes are black, so they don’t emit light, and they have a lot of mass, so that’s a good start. The trouble is that most black holes are too small, and while they don’t emit light themselves, they do whip a debris disk around them up to such an energy level that it glows with its own detectable light. We know roughly what the life cycle is for stars to turn into black holes, and it takes really big stars to start with, which go supernova at the end of their lives. The Supernova compresses a small central core of the star, which collapses to form the black hole, while the explosion expels the rest of the mass into space. As a result, stellar black holes almost never get bigger than 15 solar masses, regardless of the size of the star they form from. That’s too small to explain dark matter, given what we know about the size distribution of stars, and how long those stars take to form black holes; there just haven’t been enough black-hole-forming stars in the lifespan of the universe for this to be the explanation.

There’s a possible way around the black hole shortage, if we consider primordial black holes, which could have formed from the dense matter that filled the universe right after the Big Bang. These might be as much as 60 solar masses. However, to explain dark matter, there would need to be a lot of these black holes, enough that we should be able to detect a few by looking for gravitational lensing around them. We’ve been looking for decades, and though we have found a few unique black holes, and have not seen the level of lensing we would expect from the density of black holes that would be needed for this to be the right answer. As of 2024, primordial black holes statistically should have been detected if they accounted for any more than 60% of dark matter, and the longer we go without detecting them, the smaller that number will get.

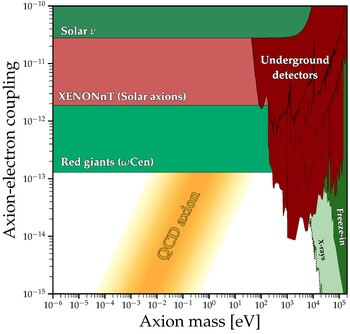

From here the potential dark matter candidates get weirder. Probably the best extant theory that still has a chance is a theoretical particle called an “axion” which I will not even pretend to understand well enough for a hot take. It’s a fan favorite among cosmologists because if it exists it would solve a problem in Quantum Chromodynamic theory and also solve dark matter in one fell swoop. As such, we’ve been doing experiments to try to find axions for about four decades now, and have found none so far. This isn’t a dead theory, though; the experiments have constrained the possible characteristics of axions, but not ruled them out entirely because the theory still works even if axions are too small for all our current instruments to detect them. So what we know is that if they exist, their mass is below a certain limit, and their ability to couple with magnetic fields is below a different limit, shown in the chart below. All the colorful zones are ruled out by various experiments, but you can still see some white space, and the gold band represents the remaining region that would work for both dark matter and QCD theory.

There are still more theories that get weirder still, but we’ve been exhaustive enough. Time for my own pet theory.

My theory: It’s actually just dark energy tricking us.

Dark energy makes up 68% of all the mass-energy content of the universe, but it is very diffuse; theoretically, it is evenly distributed throughout all of space, and provides the counter-gravitational force needed to explain the accelerating expansion of the universe.

I simply think the distribution isn’t uniform. Instead, I think that whatever material mediates dark energy is repelled by mass of any kind, including its own mass, but also including the mass of normal matter. Since normal matter condenses, attracted to itself, into planets and black holes and whatnot, the distribution of these repelled particles should not be uniform - instead, wherever there is normal matter, you would get a sort of bow shock, a halo where the dense gravity of the massive object pushes the dark energy/matter material into higher than average density, which declines with a gradient out into deep space (i.e. far from galaxies) where the self-repelling dark stuff spreads out uniformly.

Critically, in this formulation, both normal matter and the dark stuff have positive mass, there is just a force involved in the dark stuff that is repelled by positive mass. The result would be that the dark stuff would be densest right outside the edges of galaxies, and its mass would contribute to the motion of the normal matter in those regions, creating the phenomena we see with galaxies spinning too fast, higher than expected gravitational lensing, and so on.

We should be able to test this, to a certain extent - if my theory is right, then we should be able to look at the distribution of mass that would account for the galaxy motion we see, and calculate what the repelling force would need to be to achieve both the expected value of dark energy spread through all of space that isn’t galaxies and the right size halo/bow shock around galaxies to produce the motion we observe. Then we can compare that value to value of the cosmological constant needed to explain the observed accelerating expansion of the universe, and see if it agrees. If so, we’ve got a pretty decent candidate theory for both dark energy and dark matter.

And, if this is the case, then we would also have a decent explanation for why the Big Bang could happen at all without the entire universe immediately becoming a black hole - the mass-repelled dark stuff would push outward against gravity, and then provide a gravitational pull outward that would counteract the inward pull on regular matter. Thus, regular matter could escape the early universe despite being too dense to do so under its own momentum, which could not exceed lightspeed.

Seems elegant to me. I don’t know where to begin to do the math to validate it though. Anyone want to tackle it with me?